“Man Shall Not Live on Bread Alone” Unlocking the Secrets of Bread

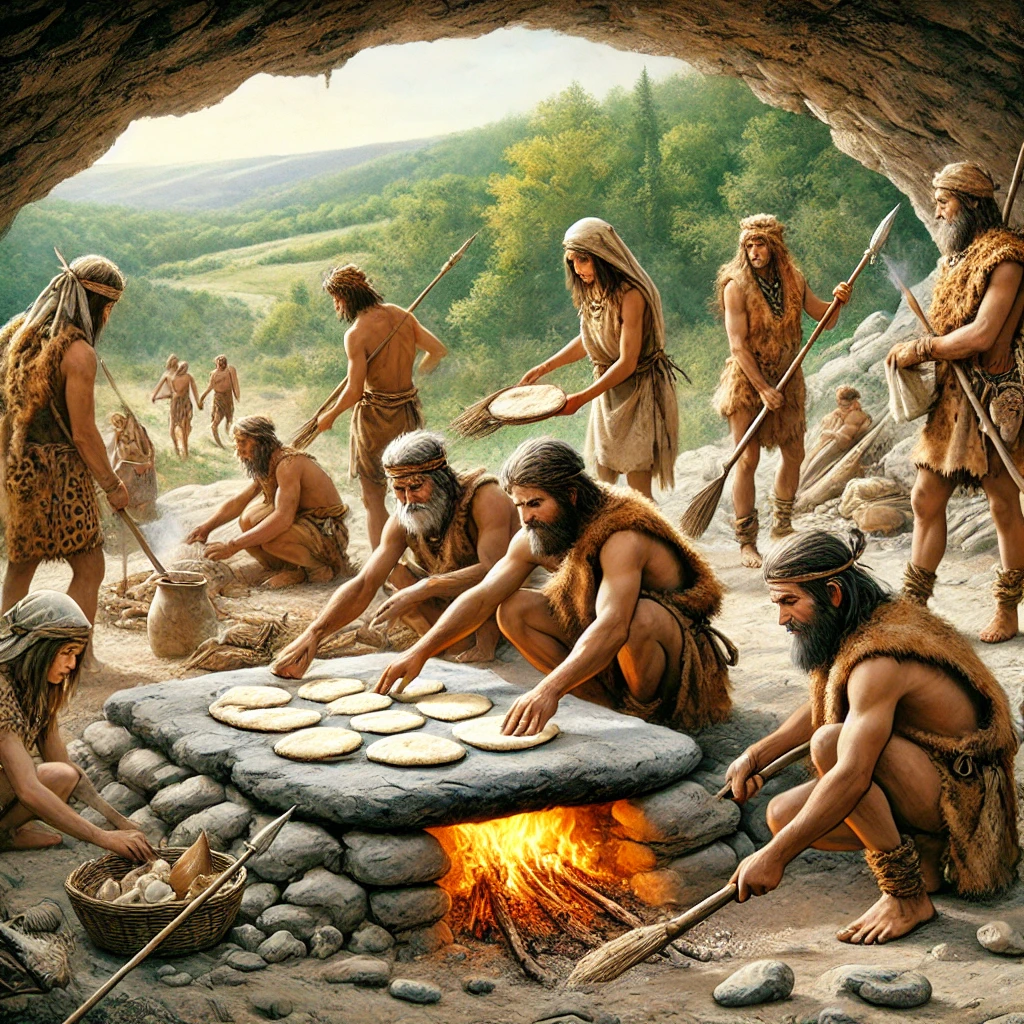

The origins of bread date back to the Neolithic era, around 10,000 BCE, when humans transitioned from hunter-gatherer societies to settled agricultural communities. Early forms of bread were likely simple flatbreads made from wild grains mixed with water and cooked on hot stones or in ashes. During the Neolithic era, bread making evolved as humans transitioned from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to settled agricultural communities. This period, roughly 10,000 to 4,000 BCE, saw the cultivation of cereals such as wheat and barley, which were ground into flour using stone tools. The flour was mixed with water to create dough, which was then baked on hot stones or in primitive clay ovens. Evidence from archaeological sites, such as charred bread remnants and grinding stones, indicates that early bread was unleavened and resembled flatbreads or porridge cakes. This innovation not only provided a reliable food source but also marked a significant advancement in food processing and dietary habits.

The origins of bread date back to the Neolithic era, around 10,000 BCE, when humans transitioned from hunter-gatherer societies to settled agricultural communities. Early forms of bread were likely simple flatbreads made from wild grains mixed with water and cooked on hot stones or in ashes. During the Neolithic era, bread making evolved as humans transitioned from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to settled agricultural communities. This period, roughly 10,000 to 4,000 BCE, saw the cultivation of cereals such as wheat and barley, which were ground into flour using stone tools. The flour was mixed with water to create dough, which was then baked on hot stones or in primitive clay ovens. Evidence from archaeological sites, such as charred bread remnants and grinding stones, indicates that early bread was unleavened and resembled flatbreads or porridge cakes. This innovation not only provided a reliable food source but also marked a significant advancement in food processing and dietary habits. The Egyptians were pioneers in the art of bread-making[i]. The Egyptians developed techniques for grinding grain into fine flour using stone mills, which improved the texture and quality of bread. Evidence suggests that ancient Egyptians discovered the process of fermentation, likely by accident. Wild yeast spores from the environment would have inoculated the dough, causing it to rise and produce a lighter, more palatable bread.

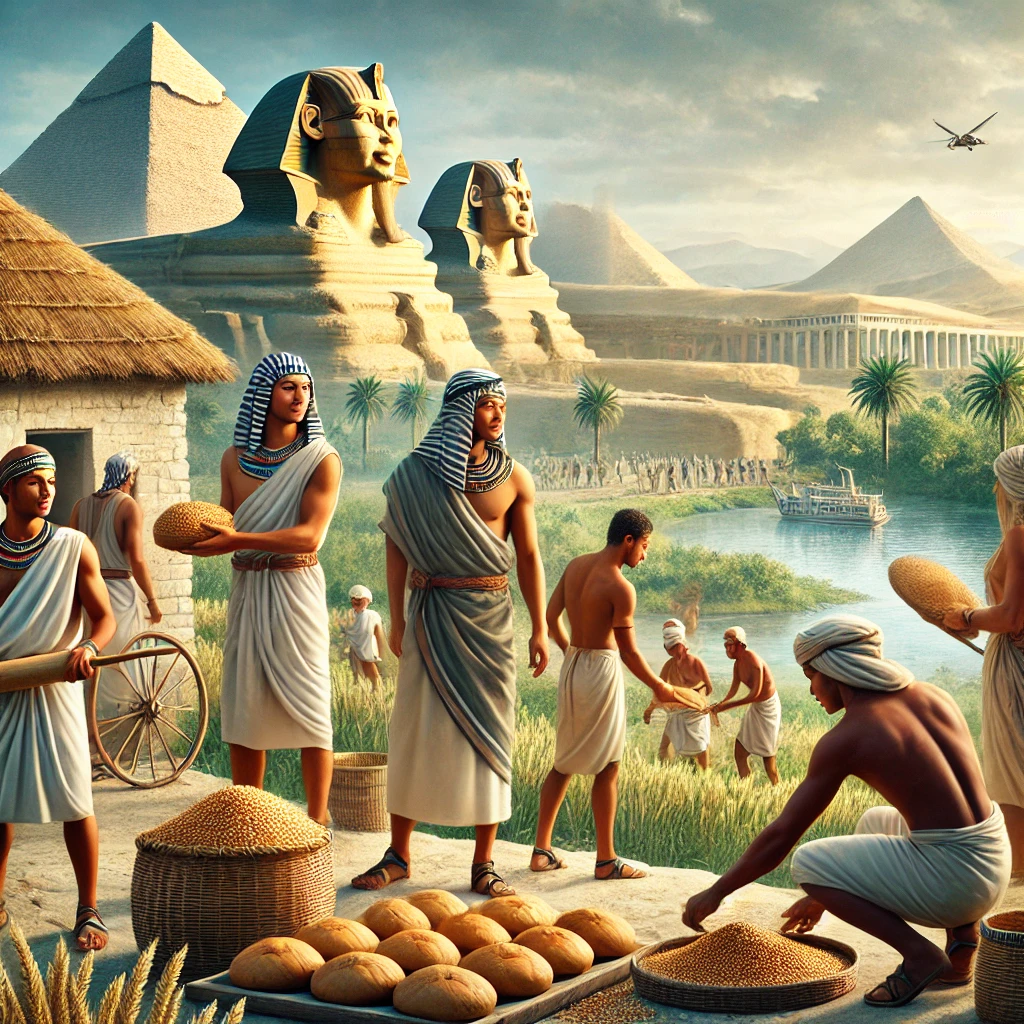

The Egyptians were pioneers in the art of bread-making[i]. The Egyptians developed techniques for grinding grain into fine flour using stone mills, which improved the texture and quality of bread. Evidence suggests that ancient Egyptians discovered the process of fermentation, likely by accident. Wild yeast spores from the environment would have inoculated the dough, causing it to rise and produce a lighter, more palatable bread.

It was a staple food for all social classes, from peasants to pharaohs[ii]. The importance of Bread was very apparent Egyptian society. It held significant cultural and religious importance in ancient Egypt. It was often included in offerings to the gods and in burial goods for the afterlife. The symbolism of bread is evident in numerous Egyptian texts and tomb paintings, underscoring its central role in both daily life and spiritual practices[iii].

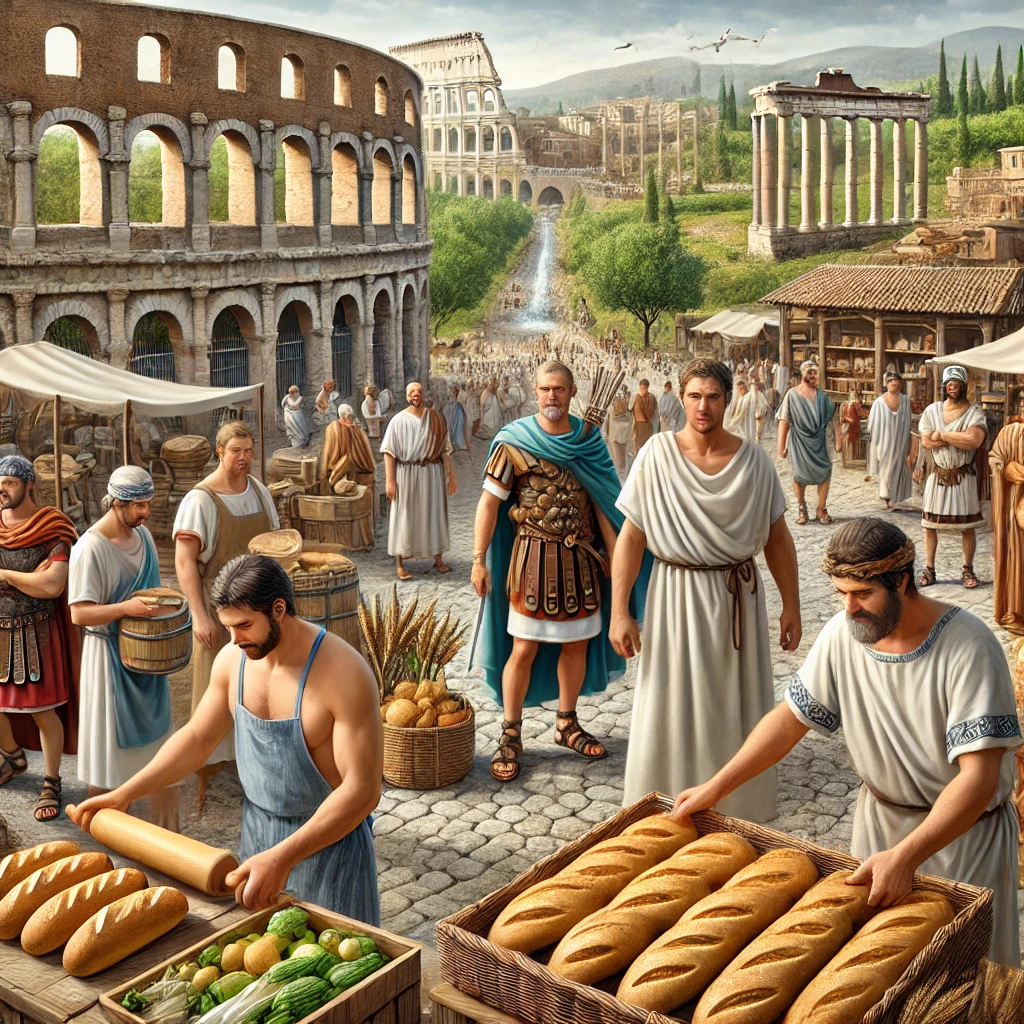

During the Roman Empire, it was consumed by all classes of citizens, from the rich to the poor. It was a staple of the Roman diet. There were many other varieties of it, including those flavored with herbs, cheese, or even honey. The widespread consumption highlighted its importance in Roman culinary culture[iv]–[v]. During the cooking process the wall that was locking it away from its beneficial effects broke down and it became a part of the final popular consumable product[vi].

During the Roman Empire, it was consumed by all classes of citizens, from the rich to the poor. It was a staple of the Roman diet. There were many other varieties of it, including those flavored with herbs, cheese, or even honey. The widespread consumption highlighted its importance in Roman culinary culture[iv]–[v]. During the cooking process the wall that was locking it away from its beneficial effects broke down and it became a part of the final popular consumable product[vi].

Bread has played a crucial role in the survival and sustenance of various human populations throughout history, particularly during times when other food sources were scarce. While it is an oversimplification to say that humanity as a whole “survived on bread,” there have been numerous instances where bread was a primary staple in the diet, providing essential calories and nutrients for survival. It keep the people healthy. Here are some notable examples;

Ancient Egypt: Emmer bread. Natural yeasts from the environment were used for raising the bread dough before baking[vii].

Ancient Rome: Panis Quadratus (wheat bread). The masses of Roman society from the Rich down to the Soldiers, commoners, and slaves relied heavily on bread. Soldiers received bread as part of their rations[viii]–[ix].

Medieval Europe: Rye bread was the staple of peasants, serfs, and lower classes who survived on it. It was made from wild yeasts with bread often being denser and less refined[x]–[xi].

Industrial Revolution: White wheat bread and mixed-grain breads. Working-class populations in rapidly industrializing cities relied on cheap, mass-produced bread. Baker’s yeast became more commonly used due to advances in baking technology[xii].

Industrial Revolution: White wheat bread and mixed-grain breads. Working-class populations in rapidly industrializing cities relied on cheap, mass-produced bread. Baker’s yeast became more commonly used due to advances in baking technology[xii].

World War II: Rationed bread made from a mix of available grains, often referred to as “war bread.” Civilians and soldiers in war-torn countries relied on bread as a primary food source due to rationing and food shortages[xiii].

As you can see, bread is an important part of the history and survival of our species, from the time of the recorded history of Joseph, and his interpretation of the dreams of the pharaoh, to present day “science”.

What did Egyptians and Romans know that modern society may have forgotten, or lost?

However, what is the secret the baking of bread unlocks?

When the dough is being created and then baked, the fermentation, mixing, kneading, proofing (dough rises) and baking break down the baker’s yeast cells. The cell walls, which contain a specific molecular structure that remains intact[xiv]–[xv]–[xvi]–[xvii]–[xviii].

This structure has been shown to be very beneficial for maintaining a healthy immune system in numerous published peer-reviewed studies, stretching back to the 1950’s on practically every disease known to humanity and is as safe as eating a high-quality organic bread.

What is the Specific Molecular Structure that Remains that is so Beneficial to Human Health?

NEXT>>>

Citations

[i] Samuel, D. (1996). Investigations of ancient Egyptian baking and brewing methods by microscopic analysis and experimental archaeology. Journal of Archaeological Science, 23(1), 7-12. doi:10.1006/jasc.1996.0002

[ii] Pomeroy, S. B., Burstein, S. M., Donlan, W., & Roberts, J. T. (2008). Ancient Egypt: A Social History. Oxford University Press.

[iii] Rice, M. (2003). Egypt’s Making: The Origins of Ancient Egypt 5000-2000 BC. Routledge.

[iv] Curtis, R. I. (2001). Ancient Food Technology. Brill.

[v] Erdkamp, P. (2005). The Grain Market in the Roman Empire: A Social, Political and Economic Study. Cambridge University Press

[vi] Fleet GH. Yeasts in dairy products. J Appl Bacteriol. 1990 Mar;68(3):199-211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1990.tb02566.x. PMID: 2187843. https://www.sci-hub.ru/10.1111/j.1365-2672.1990.tb02566.x

[vii] Curtis, R. I. (2001). Ancient Food Technology. Brill.

[viii] Erdkamp, P. (2005). The Grain Market in the Roman Empire: A Social, Political and Economic Study. Cambridge University Press.

[ix] Fleet, G. H. (1992). “Yeasts in dairy products.” Journal of Applied Bacteriology, 73(1), 95-107. https://www.sci-hub.ru/10.1111/j.1365-2672.1990.tb02566.x

[x] Curtis, R. I. (2001). Ancient Food Technology. Brill.

[xi] Davidson, A. (2014). The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford University Press

[xii] Kaplan, S. L. (2006). Good Bread Is Back: A Contemporary History of French Bread, the Way It Is Made, and the People Who Make It. Duke University Press.

[xiii] Davidson, A. (2014). The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford University Press.

[xiv] Fleet, G. H. (1992). The microbiology of brewing. In Brewline yeast and bacteria (pp. 1-51). Springer, Boston, MA. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-0643-5_1

[xv] Kulp, K., & Lorenz, K. (2003). Handbook of Dough Fermentation. CRC Press.

[xvi] Kogan, G., & Kocher, A. (2007). “Role of yeast cell wall polysaccharides in pig nutrition and health protection.” Livestock Science, 109(1-3), 161-165.

[xvii] Steensels, J., & Verstrepen, K. J. (2014). Taming wild yeast: potential of conventional and nonconventional yeasts in industrial fermentations. Annual Review of Microbiology, 68, 61-80. doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-091213-113025

[xviii] Carlson, M., & Botstein, D. (1983). Organization of the SUC gene family in Saccharomyces. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 3(3), 351-359. doi:10.1128/mcb.3.3.351